As I’ve mentioned a number of times in previous posts, I use Wiktionary extensively in the course of my etymological research. I recognize Wiktionary as a most valuable resource for finding reconstructions of Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Celtic and Proto-Germanic words. But I am often annoyed at the many instances of erroneous information presented in these reconstructions, some of which is due to the pronouncements of recognized experts.

One of the more annoying instances of erroneous information in etymological reconstructions is the idea that Proto-Indo-European ei became ē in Proto-Celtic. I’ve dealt with this bothersome error in this post: https://vellaunos.ca/2021/03/27/on-proto-celtic-ei/ Another instance of erroneous information in etymological reconstructions that I find equally annoying is the Proto-Celtic –ākos adjective suffix. There is no doubt in my mind that this was most certainly –akos with a short a in Proto-Celtic. In fact, I see no good reason to believe that this Proto-Celtic suffix was –ākos rather than –akos.

The only modern Celtic language that appears to regularly show a reflex of –ākos is Welsh, which has –og. Its close cousins Breton and Cornish have –ek/-eg and –ek (respectively), these apparently being from Old Breton and Old Cornish –oc – a form which does apparently indicate a Proto-Brittonic –og (yet one would expect that –euk and –eug would be the regular reflexes of an original –ākos in Modern Breton).

Turning to Old Irish, we find that the cognate of Brittonic –og is –ach with a short a. Old Irish did also have a form –óg, but it is obvious (and commonly admitted) that this resulted from a borrowing of Brittonic –og. I’m quite sure that Old Irish –ach with a short a reflects –akos rather than –ākos; that is to say that I don’t know of any reason why –ākos would have resulted in –ach rather than –ách in Old Irish.

Outside of the Celtic branch, we find –agaz with short a in Germanic (as well as –igaz with short i), –icus with short i in Latin, and –ikos with short i in Greek. These suffixes and all other cognate suffixes in other Indo-European branches all begin with short vowels. Interestingly, the Wiktionary page on Proto-Celtic –ākos (https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Reconstruction:Proto-Celtic/-ākos) gives Latin –ācus and –īcus as cognates, but the linked page for –ācus doesn’t exist (I wonder why) and the link for –īcus goes to a page that has only –icus, not –īcus.

The Wiktionary page for Proto-Celtic –ākos gives an interesting derivation from Proto-Indo-European –eh2-kos/-eh2-kjos with (presumably) the feminine ending –eh2 before the adjective suffix –kos/-kjos, but there is nothing like this anywhere in the rest of the Indo-European language family [*** but see the addendum below ***]. And in fact, it hardly makes sense since the vowel between the end of the word stem and the adjective suffix is not indicative of gender, gender endings being incorporated in the suffix itself (i.e. –kos, –keh2, –kom) (in fact, this vowel is essentially an epenthetic vowel).

The Proto-Brittonic –og could reflect an original –ākos; however, this –ākos could be a Brittonic innovation rather than a common feature of Proto-Celtic. But in fact, it seems to me that Proto-Brittonic –og resulted from an earlier Proto-Brittonic –āg that itself resulted from –akos that was stressed on the a (for example, *woltákos “hairy” > *gwoltāg > *gwaltog (Welsh gwalltog) – compare Old Irish foltach). [Note the change from o–ā to a–o in this particular Brittonic word.]

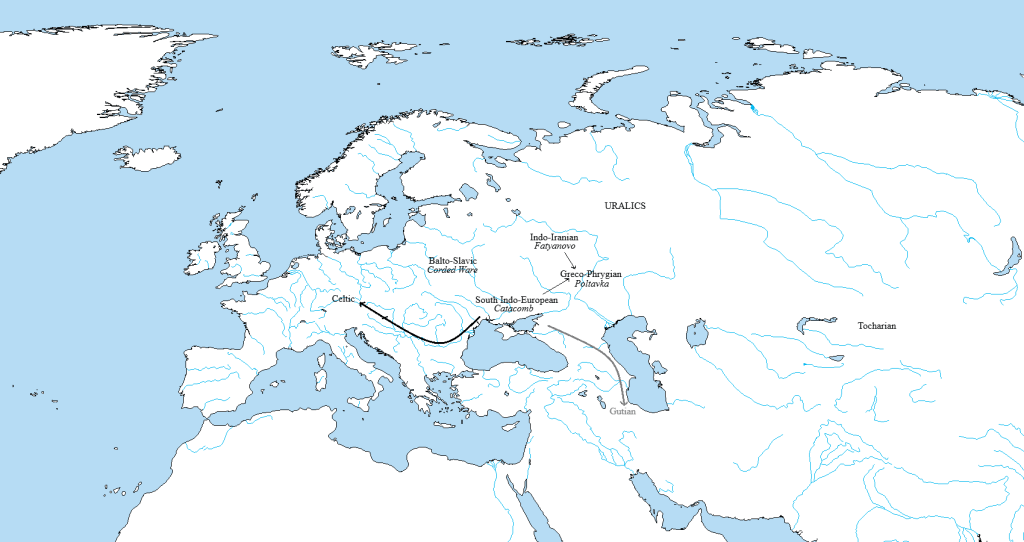

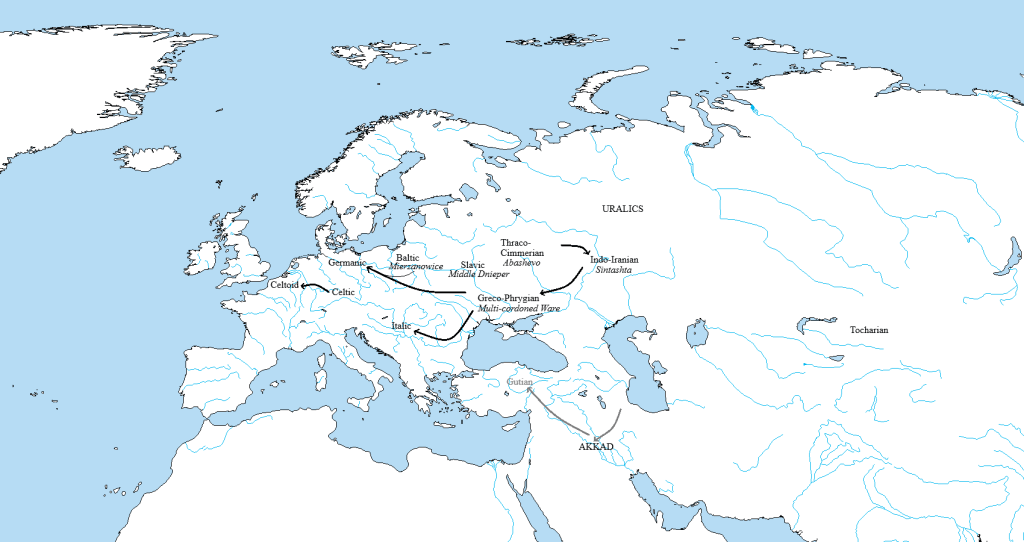

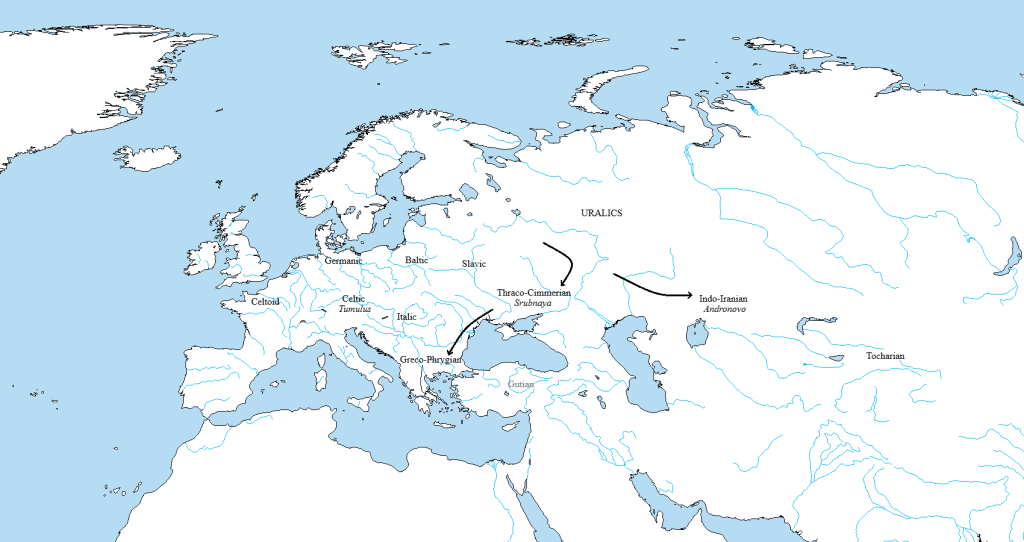

It could be that stress on the penultimate syllable was a regular feature of the Celtic spoken in Britain in Antiquity (i.e. British Celtoid), and it may also be that this was a regular feature of Continental Celtic (i.e. Celtic properly speaking) – this being a possible instance of Celtic influence on British Celtoid (see https://vellaunos.ca/2021/03/26/celtic-and-celtoid/). I speculate that the loss of final syllables in Proto-Brittonic might have caused the lengthening of short vowels in the still-stressed now-final syllables that were previously penultimate syllables – at least in some cases (other examples of this might be *epalos “foal” > Proto-Brittonic *ebāl (Welsh ebol), *olinā “elbow” > Proto-Brittonic *œlīn (Welsh elin) and *ongwinā “nail” > Proto-Brittonic *œ(ŋ)wīn (Welsh ewin)). I might speculate further that this might have happened in Continental Celtic as well if it had survived Antiquity and had also undergone the loss of its final syllables.

[Addendum – July 25, 2022]

In the third-last paragraph above in which I discussed the supposed *-eh2-ko– form that presumably produced the Proto-Celtic *-ākos suffix, I stated that “there is nothing like this anywhere in the rest of the Indo-European language family”. Well, it occurred to me this morning that there might be something like this in Latin, this being the –ōx suffix in the adjectives ferōx ‘fierce’ and atrōx ‘terrible’.

The usual explanation for this Latin –ōx suffix is that it represents *h3ekw-s ‘eye’, so that ferōx (gs ferōcis) and atrōx (gs atrōcis) would originally have meant something like “wild-animal eyed” and “fire eyed” (respectively). Although such an explanation is certainly not impossible, it has always looked like a silly folk-etymology to me, and I frankly have some difficulty taking it seriously. [The de-labialization of –kw– is obviously not an issue, this having happened in Latin vōx (gs vōcis) from *wōkw-s.]

What I propose instead as a possible explanation for this Latin –ōx suffix is *-oh1k-s. This suffix may also be found in reduced grade – *-h1k-s – in Latin senex ‘old’ and iūdex ‘judge’. A thematized form of this reduced grade *-h1k-s – *-h1k-os – may in fact be the origin of the Germanic *-agaz/*-igaz, Latin –icus and Greek –ikos mentioned above.

[By the way, I don’t agree with the etymology *jouoz-dik-s for Latin iūdex, *-dik– presumably being from *deikj– ‘point to, indicate’. Again, this looks to me like a silly folk-etymology. Instead, I suggest *jouz-dhh1– “right-put” (the reduced grade of *dheh1– ‘put, place’ being regularly used as a suffix) with the *-h1k-s suffix – *jouz-dhh1-(h1)k-s.]

[Another supposed instance of *h3ekw-s used as a suffix is represented by Latin antīquus ‘ancient’ and Sanskrit antika ‘vicinity, proximity’, both presumably coming from *h2enti-h3kw-o-. Whereas the Sanskrit reflects the original sense of *h2enti– ‘against, adjacent’ (derived from *h2en– ‘on’), the Latin antīquus clearly reflects the shift in meaning of Latin ante ‘before’. In any case, it’s hard to see how either “against-eye” or “before-eye” can be equivalent to “ancient”. So, although the *h2enti-h3kw-o– etymology is not impossible, I much prefer to propose *h2ent-h1k-o– (“adjacent, close”) as the origin of Sanskrit antika and *h2enti-h1k-wo– (“being of before”) as the origin of Latin antīquus.]

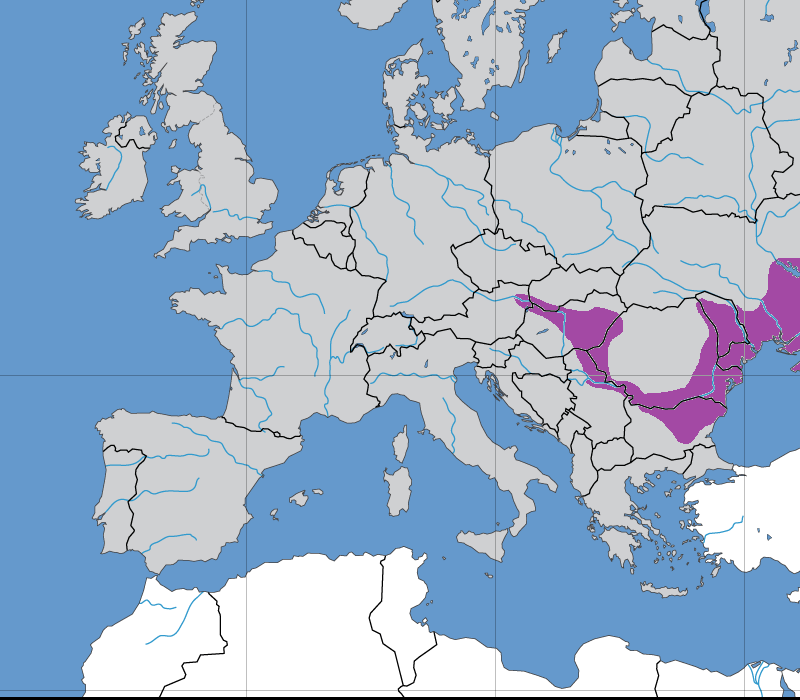

Turning back to the presumed Proto-Celtic *-ākos suffix, it may be that this in fact existed and that it was related to the Latin –ōx suffix. What we might have here is *-oh1k-s becoming *-ōks, then being thematized to *-ōkos and finally becoming *-ākos in Celtic. [The thematization of this suffix obviously occurred before *-ks– became *-xs.] Given the possibility that reflexes of this *-oh1k-s suffix are found in both Italic and Celtic, I propose that it might have been a common South Proto-Indo-European innovation.

So, I might well have been mistaken in suggesting that the *-ākos suffix didn’t exist in Celtic. However, I suspect that *-akos with a short a probably also existed in Proto-Celtic given that corresponding forms with short vowels existed throughout the Indo-European language family, including the other South Proto-Indo-European groups (Italic, Germanic (partly) and Greek (partly)). I might further admit the possibility that the *-ākos form eventually replaced the *-akos form entirely in Celtic, and that this also happened in Brittonic Celtoid under the influence of Celtic, but that it didn’t happen in Goidelic Celtoid, Old Irish having –ach instead of **-ách.